Imagine if the brain was a biological organ

Toxic society as a cause of mental illness

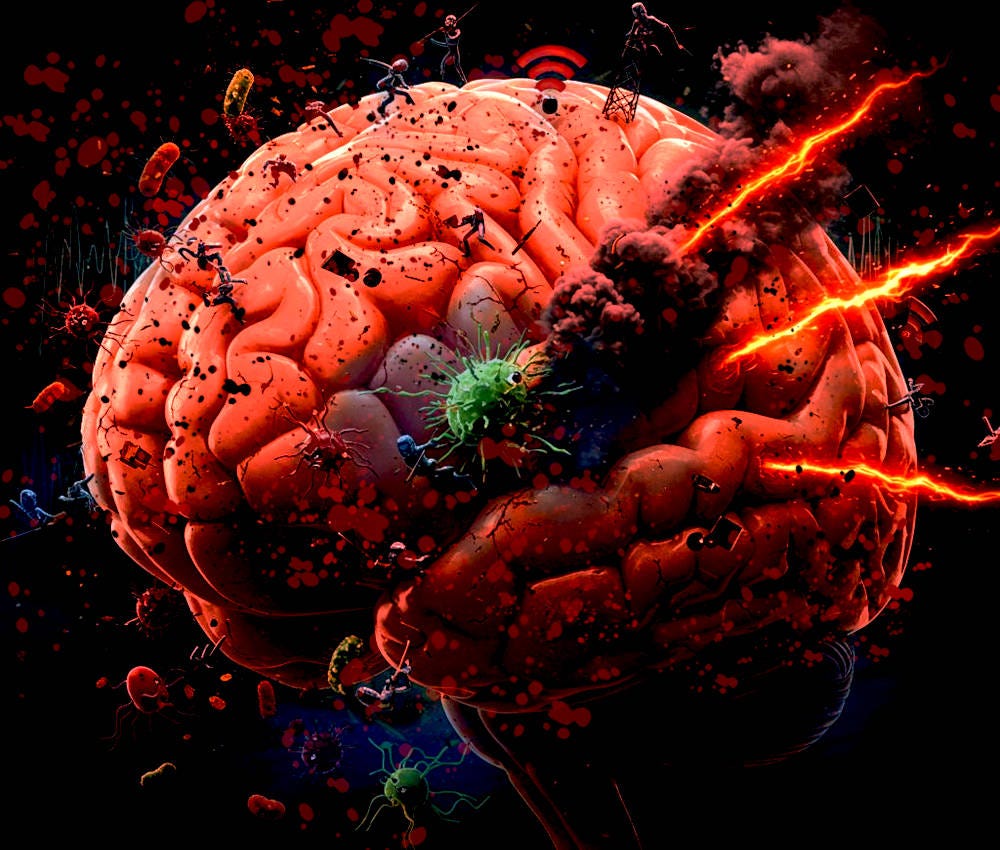

Mental illness is often approached as though it has no physical causes. Patients are fenced off from biological investigation and physical doctors, and ‘treated’ via the hocus-pocus of psychology. Ignorant laypersons, incapable of imagining the experience of others beyond their own limited exposure to life, label the mentally ill as actors, or lazy people. Yet, there is undeniable evidence that many psychiatric illnesses do have biological triggers. A significant amount of those triggers are environmental, and beyond the control of the individual patient who is suffering as a consequence.

The brain is a physical organ, but it’s difficult to assess its health. Hearts can be monitored. Renal function tested. Eyes and skin can be seen. Spleens, livers, and guts, palpated. But brains? We can’t see them, we can’t feel them, and there are very limited biomarkers available in normal bodily fluids. X-rays have inadequate resolution, and CT scans, MRI scans, or EEGs are expensive, rarely available, and limited in what they can detect. Traditionally, this has led to the dismissal of the idea of brain pathology being the main cause of mental illness. Instead, psychological health becomes the attribute of some nebulous network of concepts such as soul, attitude, values, perception etc. Often, people treat psychological distress like it’s a life choice, or an attitude, compounding the stress and abuse faced by the mentally ill.

Around 2.5 billion people out of those currently alive on Earth will suffer from mental illness during their lifetime

Inflammation has a direct causative association with psychiatric disease, correlating with severity. Our environment bombards us with a multitude of pro-inflammatory factors daily. Particulate matter in air pollution, contaminants and toxins in our food and water, cosmetic chemicals and cleaners, microwave radiation used for communications technology, and building and decorating materials are among just a few. For example, exposure to particulate matter and nitrogen oxide correlates with atrophy of the hippocampus, and dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex. Heavy metals, including mercury and lead, can lead to increased impulsivity by disrupting the balance of GABA and glutamate in the brain. Pollutants elevate pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and TNF-a, which are causally linked to the overexpression of the kynurenine pathway leading to brain activity associated with suicidal ideation.

Electro-magnetic radiation from wireless devices can alter immune function, exacerbate oxidative stress, interfere with genome integrity, and cause mitochondrial responses that add to inflammatory load. Volunteers subject to temporary exposure to 900 MHz EMR were found to have altered sleep EEG patterns. In the long-term, sleep disturbance can cause changes in brain architecture, and is often associated with recalcitrant neuropsychiatric illness. The electromagnetic field created by mains electricity has been shown to cause skin irritation. Chronic skin conditions frequently lead to significant stress and highly correlate with poor mental health.

Natural pathogens and microbial disturbance worsens the assault. Bacteria, fungi, and viruses can all lead to pro-inflammatory responses. If you had an infected area of the brain, who could see it? It would only be picked up in the most severe cases, and even then it’s often missed. Microbes, such as the single-celled Toxoplasma gondii, found everywhere, especially in cats, can cause inflammation, and increased dopamine synthesis, contributing to a higher risk of schizophrenia. Ingested toxins and agrochemicals can disrupt the gut microbiome, throwing the gut-brain axis into disarray; around 95% of serotonin, a crucial neurotransmitter, is produced in the gut, not the brain.

Physical sickness can cause neuropsychiatric symptoms, too. Most systemic physical illness will induce inflammation. Chronic disease, such as lupus and other autoimmune conditions, have been found to give rise to antibodies that attack NMDA receptors; these are ion channels in the brain whose function is crucial for learning, memory, and neuroplasticity.

Unfortunately, doctors are often unaware of their own biases, resulting in high rates of misdiagnosis for psychiatric disorders. For example, approximately 1 in 7 people diagnosed with refractory depression are found to have an undiagnosed thyroid disorder. Other conditions such as Lyme disease and B12 deficiency cause paranoia, irritability, and anxiety. Patients who present with these symptoms are frequently diagnosed with a primary mental health condition, their physical disease remaining undiagnosed and untreated. Worse still, people with diagnosed mental health conditions regularly have comorbid physical conditions ignored; there is up to a 50% reduction in the likelihood of being sent for physical tests for conditions such as cancer, heart disease, or diabetes, with symptoms dismissed as psychosomatic. The nature of mental illness significantly impairs self-advocacy.

Social hostility, isolation, and noise pollution all cause measurable physical responses, triggering biochemical signalling pathways. Repeated, or chronic exposure, can lead to pro-inflammatory conditions and morphological changes in the brain. Even non-hostile noise, including traffic noise, has been shown to trigger biological changes that damage cognitive function and increase oxidative stress, contributing to neurodegenerative disease. Much of this is outside the control of the individual, who has limited agency to effect useful change.

Prolonged, or severe, early exposure to social hostility and isolation can lead to permanent physiological changes in the brain. For example, being under conditions of chronic stress can result in reduced hippocampal volume, and inhibited prefrontal cortex connectivity. Higher cortisol levels impair the sensitivity of glucocorticoid receptors, further compounding depressive symptoms. Childhood trauma correlates with the thinning of the anterior cingulate cortex, and an adaptive response that increases amygdala activity; things associated with severe psychiatric disorders, including PTSD. Social isolation results in a higher level of inflammatory markers, including CRP and IL-1β, and diminishes ventral striatum reward responses.

There is much overlap in observed regions of brain activity between mental illness and chronic physical pain. The main difference being that the brain has no body part to associate with the pain, hence the indistinct nature of symptomatic experience, or the emergence of phantom pain, skin irritation, generalized anxiety, nausea, and so on. The brain is simply trying to locate the cause of the problem somewhere in the body so it can be dealt with. It’s not imagined, the pain is quite real. A broken bone might induce similar brain activity to the acute phase of depression; a second degree burn, that of the agonizing prolonged stage of depressive illness. Can you imagine forcing someone to walk on a broken bone and feet with second degree burns? Yet, people with significant mental health issues are often forced to engage in unwanted neurological activity. Additionally, mental illness usually exacerbates the experience of pain, making it much worse than it would be without the mental illness. To compound this, it’s common for people with mental illness to have comorbid chronic pain conditions, each exacerbating the other, making the overall experience much worse.

We aren’t all affected equally. Our response to environmental stressors, and the way the biological circuitry associated with mental illness is activated, are significantly different depending on pre-existing physical characteristics. Genetic predisposition contributes to the variable response between individuals when exposed to similar conditions. A number of genes have been linked to the emergence of mood and cognitive disorders in the modern world, including those responsible for dopamine regulation (COMT), serotonin transport (SLC6A4), and neuroplasticity (BDNF). Disorders can be inherited directly through gene transfer, or via trans-generational epigenetic changes. An unborn baby can be impacted if the mother is exposed to trauma.

Poor neurophysiological health usually impairs emotional regulation. This often leads to more conflict and stress, heightening negative, damaging social experiences for individuals exposed to low empathy, ignorant, and dismissive people. Such unhelpful traits may also accompany neuropsychiatric conditions, and run in families, creating a cauldron of disaster. Overall functional impairment has significant impact on economic opportunity, living costs, and social functioning, leading to a vastly reduced capacity for individuals to stand up for themselves, or fund beneficial circumstantial changes.

Psychological and sociological interventions can help temporarily, if done with proper care and consideration. Recognizing how much pain and difficulty a person is in, and giving them space to talk without dismissing, criticizing, or judging them is important. However, without accounting for, and addressing, underlying physical problems, such interventions will have limited efficacy. If done badly, they might be harmful. For example, imagine suggesting a depressed patient go for a walk. Something that has often been recommended to me. Get some sun and fresh air, it’ll do you good. Now, understand that this activity could expose the patient to allergens, socially hostile individuals or groups, exacerbate their arthritis, and induce prolonged physical fatigue. The result will be extremely detrimental to both their physical and mental health. More care and thoughtful consideration needs to be given before regurgitating such banal prescriptive suggestions. Better still, let the patient decide for themselves.

This toxic world costs everybody, but affects some individuals more severely through no fault of their own. Our understanding of the complex, and delicate, ways our body and brain responds to toxic and hostile elements is far from complete. However, we have enough information to know that many normalized aspects of modern living are causing harm. Wireless radiation, air pollution, and contaminated food and water, are all largely unavoidable. Some people contribute more than others to these problems, but the way our society and economy are structured, it seems inescapable that everybody will contribute in some way. As such issues become more widespread and endemic, the developing brains of children and young adults will be increasingly susceptible to damage that can cause lifelong neurological dysfunction.

This is a serious problem. Many psychiatric disorders are terminal—approximately 800 000 people kill themselves annually, others die due to indirect means. Roughly, 30 million people have ended their lives since 1980, more than the entire population of Australia in 2025. Globally, lifetime prevalence of mental illness is around 30%; that means it will affect around 2.5 billion people out of those currently alive on Earth. If you live to 75, you have a 50% chance of suffering with a clinically diagnosable mental health disorder. Mental illness causes a significant drop in life expectancy, and reduces quality of life, sometimes severely. More harms are being introduced to the world every year, often based on economic ‘need’ and reckless innovation. Some people benefit massively from these developments, but many see no improvement to their lives, and a substantial number are detrimentally affected. The people who suffer adversely as a result of this reckless civil order should rightly be compensated for the physical harms, and associated mental trauma, that they have to endure.

Further reading:

Bračko, S., & Čelofiga, A. (2024). “It’s a Psychiatric Patient”: Misdiagnosing of Somatic Symptoms in Patients with Mental Disorders Due to Stigma and Inadequate Diagnostic Treatment. Archives of Psychiatry Research: An International Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 60(1.), 62-66.

Cardenas-Iniguez, C., Burnor, E., & Herting, M. M. (2022). Neurotoxicants, the developing brain, and mental health. Biological psychiatry global open science, 2(3), 223-232.

Charney, D. S., Buxbaum, J. D., Sklar, P., & Nestler, E. J. (Eds.). (2013). Neurobiology of mental illness. Oxford University Press.

Flor, L. S., Stein, C., Gil, G. F., Khalil, M., Herbert, M., Aravkin, A. Y., ... & Gakidou, E. (2025). Health effects associated with exposure of children to physical violence, psychological violence and neglect: a Burden of Proof study. Nature Human Behaviour, 1-20.

Grummitt, L., Baldwin, J. R., Lafoa’i, J., Keyes, K. M., & Barrett, E. L. (2024). Burden of mental disorders and suicide attributable to childhood maltreatment. JAMA psychiatry, 81(8), 782-788.

Gupta, V., & Srivastava, R. (2022). 2.45 GHz microwave radiation induced oxidative stress: Role of inflammatory cytokines in regulating male fertility through estrogen receptor alpha in Gallus gallus domesticus. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 629, 61-70.

Hollander, J. A., Cory-Slechta, D. A., Jacka, F. N., Szabo, S. T., Guilarte, T. R., Bilbo, S. D., ... & Ladd-Acosta, C. (2020). Beyond the looking glass: recent advances in understanding the impact of environmental exposures on neuropsychiatric disease. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45(7), 1086-1096.

Kunugi, H. (2021). Gut microbiota and pathophysiology of depressive disorder. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 77(Suppl. 2), 11-20.

Lee, M. T., Peng, W. H., Kan, H. W., Wu, C. C., Wang, D. W., & Ho, Y. C. (2022). Neurobiology of depression: chronic stress alters the glutamatergic system in the brain—focusing on AMPA receptor. Biomedicines, 10(5), 1005.

Liu, L., Huang, B., Lu, Y., Zhao, Y., Tang, X., & Shi, Y. (2024). Interactions between electromagnetic radiation and biological systems. Iscience, 27(3).

Manukyan, A. L. (2022). Noise as a cause of neurodegenerative disorders: molecular and cellular mechanisms. Neurological Sciences, 43(5), 2983-2993.

Mehterov, N., Minchev, D., Gevezova, M., Sarafian, V., & Maes, M. (2022). Interactions among brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neuroimmune pathways are key components of the major psychiatric disorders. Molecular neurobiology, 59(8), 4926-4952.

Mumtaz, S., Rana, J. N., Choi, E. H., & Han, I. (2022). Microwave radiation and the brain: Mechanisms, current status, and future prospects. International journal of molecular sciences, 23(16), 9288.

Nabi, M., & Tabassum, N. (2022). Role of environmental toxicants on neurodegenerative disorders. Frontiers in toxicology, 4, 837579.

Nogo, D., Wilkialis, L., Lui, L. M., Nasri, F., Rosenblat, J. D., & McIntyre, R. S. (2021). Examining the association between inflammation and motivational anhedonia in neuropsychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 33(3), 193-206.

Rauh, V. A., & Margolis, A. E. (2016). Research review: environmental exposures, neurodevelopment, and child mental health–new paradigms for the study of brain and behavioral effects. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(7), 775-793.

Sarno, E., Moeser, A. J., & Robison, A. J. (2021). Neuroimmunology of depression. In Advances in pharmacology (Vol. 91, pp. 259-292). Academic Press.

Sequeira, M. K., & Bolton, J. L. (2023). Stressed Microglia: neuroendocrine–neuroimmune interactions in the stress response. Endocrinology, 164(7), bqad088.

Szilágyi, Z., Németh, Z., Bakos, J., Kubinyi, G., Necz, P. P., Szabó, E., ... & Selmaoui, B. (2023). Assessment of inflammation in 3D reconstructed human skin exposed to combined exposure to ultraviolet and Wi-Fi radiation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(3), 2853.

Thylur, D. S., & Goldsmith, D. R. (2022). Brick by brick: Building a transdiagnostic understanding of inflammation in psychiatry. Harvard review of psychiatry, 30(1), 40-53.

Wu, H., Wang, J., Teng, T., Yin, B., He, Y., Jiang, Y., ... & Zhou, X. (2023). Biomarkers of intestinal permeability and blood-brain barrier permeability in adolescents with major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 323, 659-666.

Yadav, H., Sharma, R. S., & Singh, R. (2022). Immunotoxicity of radiofrequency radiation. Environmental Pollution, 309, 119793.